In this weeks SFC session we explored the medical, charity and social model of disability and it effects that it has of disabled people. Some of the comments from participants included;

“The medical model makes me so angry”. “The HSE forces us to use the medical model to get the equipment we need to enable us to live our lives”

The charity model of disability was then explored. For those that don’t know what this is – again created by non-disabled people, this depicts us as again tragic and again pitiful and is used to use and exploit us to fundraise. Again disability is seen as the problem of the body and good non-disabled people should pity us and give disability services/organisations (run by non-disabled people) monies to “service us”). The impact of this model as told by participants include:

“loneliness”

“our impairments have to be cured”

“victims of our impairments”

Other comments – “you poor pet” – we might be “lucky” and get a pat on the head, we can’t take part in “normal” everyday things and of course we “cannot learn” so we cannot work.

“The medical model is like being in a Straight jacket”

As quoted by Peter Kearns

“the key to unlocking this process of transformation of disabling barriers lies in the knowledge & life experience of disabled activists working from the social model. This is why WE are experts of the ’Lived-Experience’ and need to take the lead as Disabled-Activists at all stages of Transformation of disabling Societal oppression”.

The Importance of the Social Model – Colin Barnes

Last Tuesday evening seen the end of last year’s Strategies for Change Programme, and to mark this event, we had Professor Colin Barnes come and talk to us about the importance of understanding the Social Model of Disability and using its language.

Our Chairperson – Des Kenny opened the event by congratulating all the Strategies for Change Graduate’s. He told us that

“it wasn’t so easy to get a collective of disabled people together anymore… years ago you could find us in special schools or special centres, and we found ways to organise, but this is no anymore… things have changed and ILMI had to figure out a way to reach out nationally and we did!”

Zoom made it possible for us to build relationships with disabled people, and through Strategies for Change we reached disabled people from across Ireland to collectively learn to strategise and have one voice.

Part of Strategies for Change is about continuing the work of what

“many of us started in the early years of the movement – transforming disability services, disability policy & law, to bring about change…”

Strategies for Change has planted the seeds of collective activism, so go germinate, share your knowledge, build solidarity, work collectively, and be the “change-makers that we know you have become”.

Over to Visiting Professor Colin Barnes

Colin was born blind, and both his parents were disabled. Colin told us that he

“was never brought up to feel different…my parents understood what the world was about and they knew that having an impairment wasn’t the problem… it was the way society was organised.

Colin’s dad worked in a sheltered workshop for blind people, and his mother had a mental health illness and was in and out of hospitals all her life, but otherwise he “had a great childhood”. He did tell us that he went to special school up until he was eleven “and hated it” but then he went to an ordinary school “it was the best school ever” even though he never seen the blackboard.

Colin left school at the age of 15 “with no qualifications”. He went to work in the catering industry, stayed here for a number of years, did some night schooling and achieved “three O Levels”. In 1980, Colin went to Teacher Training College and while here, he developed a course to teach “disabled kids how not to be disabled and survive in a non-disabled world”. Colin lived all his life as a “disabled person” and subsequently “knew in a sense, what the social model of disability was all about. This training course was about helping disabled kids to survive, develop their life skills, and help them to request support when needed “without being patronizing”. Colin went on to say that a “chap at the college” liked what he was doing and suggested that that Colin do further study.

Subsequently, Colin applied to Leeds University (department of sociology) and requested that he study sociology with an interest in “disability”. He was told “yes” but “had to pass an entry exam” and the rest is history.

Colin completed three years as an undergraduate (1982), and produced a dissertation called Sociology of Disability, Discrimination, and Disabled People. He told us that this research was profoundly inspired by the emerging Disabled People’s Movement:

- 1981 was the International Year of Disabled People and to mark this, there was a conference in South America. It was the first ever International Conference for Disabled People – Disabled People International – DPI (see – www.disabledpeoplesinternational.org) and over forty organisations from all over the world attended and it proved very influential

- 1980’s was the International Decade of Disabled People (see – www.un.org/development – History of United Nations and Persons with Disabilities – United Nations Decade of Disabled Persons: 1983 – 1992).

Attending this conference was an English organisation called the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS). This group came together in1974 and it was an organisation of disabled people.

The group was made up of disabled people living in long-term institutions and they were all wants change. They decided that there was a need to split individual impairments from societal responses to people with impairments, which meant that everything including language was turned upside down:

- Impairment is defined by a persons physical, cognitive or mental health condition

- Disability is defined as the barriers or problems that are created by society (see – www.disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk – UPIAS-UPIAS.pdf).

Colin believes that impairment is just part of life, especially if people live into their older years – most disabled people also acquire their impairments through accidents or the aging process – Colin for example is losing his hearing, but this is just “part of getting older”. So, impairment is “a common experience but disability is not”.

Also, important here is that impairment can affect the “rich or poor” but it’s easier for a rich person to be disabled then it is for a poor person. The real lesson here is “that we can make things better for people with impairments and that is what the Social Model is about”. For example, having access to; large print; braille; easy read, audio description; level access, lifts; tactile surfaces etc., this the Social Model of Disability at work – changing those disabling barriers, be it physical, attitudinal, or cultural and this is what Disability Activism is all about.

Language also comes into play here, how we describe ourselves, if we say I am a person with a disability this implies that “my disability is my fault and my responsibility, I need to change” (internalised ableism – see – www.youtube.com – Internalised Ablism) – so society is off the hook. But if we describe ourselves as “disabled people/person this means that you/we are becoming part of the movement for change” because you/we are adopting a social model approach, and this is a political stance. Disability is a political issue, be it personal or collective (see – www.novaramedia.com – Disability its political).

Other important points in this conversation include:

- Those that define/describe themselves as disabled people ensues that they are not ashamed of “being a person with an impairment because it’s simply part of life. Colin told us that it is so easy to fall into the trap of feeling responsible for both your impairment and the difficulties/barriers that you encounter because of all the beforementioned but this is a trap as it ignores societal responsibilities

- Needing human support in the form of personal assistance is a reality for some disabled people but this is not “dependence”. The idea that some disabled people are more dependent than other people is fabricated, we are all dependent on other people, it is part of life, is part of being human, we cannot survive on our own and if we think about personal assistance, lots of disabled people also offer employment to many people.

Let us go back to the rich for a minute. So, the wealthier you are, the more powerful you are, but the more dependent you become – think about the Royal Family or the gentry for example, “they are the most dependent people in the world”. In olden days they would have employed people to help them to dress, undress, wash, cook, clean, organise, regardless of ability.

“Having paid support was part and parcel of who they were, some of them don’t even, to this day, choose the clothes, but we do not judge, they don’t experience disability, and it’s quite normal for them”.

Accordingly, the idea of “society providing services is not unusual” hence the Social Model of Disability in inverted comma’s Independent Living is all about having access to personal assistance (PA) where required – needing PA is not a weakness, it is a strength.

It is also not unusual for Governments that experience economic difficulties to interrupt services for disabled people. But the reality is that government’s do have and can find the monies “given political action”.

Disabled Activists are grassroots thinkers, that mobilize and rally together, using Social Model language to influence real social change for all disabled people.

Colin has written over 84 disability related articles and twenty books. The most exciting books that Colin has written includes:

- PhD Research – Cabbage Syndrome – Barnes, Colin (1990) Cabbage Syndrome – www.disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk – The Disability Archive

- Disabled people in Britain and Discrimination (1991) – www.disability.disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk – The Disability Archive

Colin also mentioned an upcoming Injustice International’ Convention Event – see – www.injustice-intl.org – Copy of call for abstracts papers-1

CCI Workshop | (In)Justice International

Find out about our upcoming conventions, conferences and workshops on injustice, Leeds. Contact our team for further information today. www.injustice-intl.org

Other Information about Colin

Colin established the Centre for Disability Studies in Leeds (see – www.disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk) and was their Director up until 2008. He also founded the independent publisher: The Disability Press in 1996 and an electronic archive of writings on disability issues: The Disability Archive UK in 1999 (see – www.disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk – The Disability Library).

Damien Walshe (CEO), closed the session, by thanking participants for sticking it out, it wasn’t easy, taking part in 26 sessions – it is a real testament to your commitment to making Ireland a better place for disabled people. He went on to say that he is very excited to see what this group will do this year.

Damien concluded by thanking ILMI staff – the 2 James, Peter, Fiona, its members – Aisling Glynn, Ellis Parmer, Eileen Daly, Colm Wholley, its board members – Jacqui Brown, Des Kenny, & Selina Bonnie and ILMI’s allies – Niall Crowley, Laurence Cox, Aileen O’Corroll and her team, Elis Barry, the people in IHREC, & Eilinior Flynn for making Strategies for Change such a huge success.

Please note that people will be able to view this recording on our webpage very soon…

A few weeks ago, we had Phil Friend from the UK come and talk to us about understanding the importance of the Social Model of Disability. Phil kicked off the session by telling us that he contracted polio at the age of three and spent three months in an iron lung as he was unable to breathe. After this he spent three years in hospital “being so called rehabed and then went off too special school where he stayed until he was 16”.

He left school with no qualifications, but his mother organised an interview for him in the Civil Service – “it was a safe place to work, you never got sacked, you could be rubbish at your job, but nobody really cared”. His mum believed that this would be a “fitting job” for Phil, so off they went to the interview, “I answered most of the questions, as my mum sat in the interview and made sure that I didn’t muck it up – I got the job”. It was a good thing back then because you got the opportunity to go to college. Phil got his “little bits of paper” and ended up qualifying as a childcare officer/social worker. He then worked his way up the ladder to become the principal of an approved/reform school – large institution with lots of naughty people in it but he loved it. But the 80’s came and Margaret Thatcher and as a result (see – www.bbc.com – What is Thatcherism?) Phil was made redundant like a lot of other people and he had to find work – wife, kids, mortgage.

Phil went to a meeting about disabled children one day (as he was a childcare officer – never worked with disabled children) and at this meeting one of the delegates asked him “why was he pretending to be normal”. Phil was intrigued, so he asked her what she meant, they had lunch and she explained that disabled people face discrimination daily. He knew that this wasn’t right and as a result got involved in the disability movement in the late eighties. And of course, once he started to “hang out with a few of these so-called disabled people my eyes were well and truly opened” and it made him “bloody furious” – furious about what was going on. So, Phil channelled his frustration in setting up a business which looked at employment opportunities for disabled people.

Phil was also very involved (as a disability activist) in the implementation of the Disability Discrimination Act and became Chair of Disability Rights UK. He is still involved although he is semi-retired and is currently the Chair of the Richard Research Institute for Disabled Consumers and is Vice Chair of the Activity Alliance – supporting disabled people to become more physically active – see –www.activityalliance.org.uk – How we-help & (www.youtube.com – Making active lives possible).

Phil invited the group to answer a question – “there is no such thing as a normal person, do you agree or disagree?

All agreed that there is no such thing as a normal person – Phil found this very interesting because he didn’t define what normal was, for example, if “I told you that it is normal to be a man then I’m guessing women are going to disagree”, “if I told you that it is normal to be 6 foot 3 most of us are going to disagree”. So let us establish that the word “normal” is used an enormous amount and in all walks of life but when it’s applied to disabled people it is a “judgmental statement” – “there is normal and abnormal”- see – www.pwd.org.au – Social Model of Disability).

Historically (as we all know) disabled people were and still are “considered by society as abnormal and going back to the 40’s there were other labels used – “cripple, invalid, mad, subnormal, educationally subnormal, spastic” and regardless of where you lived (be it Ireland or elsewhere) disabled people were seen as “less than and not viewed in a positive way. But this has all changed, we (disabled people) are now deciding what we want to be called.

The Social Model of Disability is “our definition of what disability means to us – not non-disabled people’s definition. In the 1960s and 1970s both in the UK and in America (late 1980’s in Ireland) groups of disabled people began to say, “we are not having this anymore, we are fed-up with having no rights, we are fed-up with not being considered as equals, we are fed-up with being treated differently, we are fed-up of been viewed negatively, and fed-up with been seen as a burden”.

We were deemed expendable back then – we couldn’t contribute and if we were not deemed expendable, we were pitted or felt sorry for. So whichever way we were looked upon “we were screwed”. (Phil told us that he is involved in a campaign called “Not Dead Yet UK – see (www.notdeadyetuk.org & www.ilmi.ie – UK Not Dead Yet), which is about rebelling against assisted suicide. And “Oh My God, in Canada for example they have now worked out that it is much cheaper to kill a disabled person than it is to give them palliative care – the drugs cost far less”).

Hence the beginnings of the Disabled People’s Movement – collectively disabled people talked about claiming their rights back – Mike Oliver – see (www.youtube.com – Social Model of Disability with Mike Oliver) and Vic finkelstein – see – (www.independentliving.org – To Deny or Not to Deny Disability – What is disability?) were two of these disabled people in the UK, both academic’s and both contributed to “social model thinking”, there was also Jenny Morris – see (www.disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk – Pride and Prejudice.pdf), Jane Campbell – see – (www.bbc.co.uk – Meet the ‘Vulnerables’: Baroness Jane Campbell).

From Ireland there was Martin Naughton, Joe T Mooney, Donal Toolan, John Doyle, Ursula Hegarty, Florence Dougall – see – (www.ilmi.ie – By us with-us).

All these people were saying that we are much more than disabled people, and disability does not and should not define us. We were and are, women, men, children, gay, straight, black, white, mothers, fathers, grandparents, etc. Disabled people were repositioning themselves and getting organised to demand their rights.

In 1977 (in America) 150 plus disabled people took over one of the federal offices and refused to move – it was a direct-action campaign for civil rights for disabled people – see (www.bbc.com The disabled activist who led a historic 24-day sit-in). This was “civil disobedience” – they were not getting the support they needed, – and forced the government to pass a federal law which meant that federal funding could not be given to any project unless disability was part of it. This was a massive step forward because what it meant was that funding were made available. The British & Irish experience was somewhat different as we had a so-called welfare state and we had hundreds of charities (in Ireland we had the church) “which serviced or looked after disabled people”. News travelled far and wide and disabled people from all over the world used this as a bedrock to kick start and demand their right to live good lives.

Social Model Thinking

So, the Social Model of Disability is our view. And what Mike, Vic (and many others) did was to deal with the situation in an academic way. And the first thing that these people did was to tackle medical model thinking and the notion that doctors and other professionals were the so called “experts”. Phil told us that he contracted diabetes a little while ago, so the doctor told him that he couldn’t eat biscuits, sweet things or chocolates and his reply was…” okay, thank you…let me just get one thing clear, I want you to tell me what happens if I eat these. I don’t want you to tell me that I can’t eat them, your job is not to tell me how to live my life, your job is to tell me what will happen if I eat sugar and then I will make my own decision” thank you very much.

Medical professionals have been the experts for far too long. They have been allowed to “hold the power”. Phil was sent to a special school – “signed off by a doctor, not a teacher – he was sent because he had polio – this was nothing got to do with intelligence or his ability to learn”. Now we all know that doctors have their place, but it doesn’t mean or shouldn’t mean that they are “our gatekeepers” to living like everyone else. We (the disabled people’s movement) have been trying to shift medical opinion to “doctors supporting us with our impairments/condition/s while helping us to live our life to the full”.

The second thing that these guys did was to tackle the negative stereotypes and the “tragedy & charity” systems that perpetuates difference – the idea that we were dependent on non-disabled people to “look after us” and service us (passive recipients) and that good non-disabled people would run marathons or host fundraisers and we had to feel and be grateful. All these notions were under attack because of social model thinking – see – (www.youtube.com – Piss on Pity film screening discussion).

The social model thinking approach was about separating impairment/condition and disability – see – (www.the-ndaca.org – Fundamental Principles of Disability). We are disabled people, so, for example “my (Phil) impairment/condition is polio” but “my disability” are the barriers that I face/experience because I live in a non-disabled world, and these are two very distinct things. Our impairments are real, and we do have to manage them (with support from doctor’s and other clinicians) but it’s the “disability bit” that we need to really focus on as disabled people that want change.

Phil has no conscious memory of not being disabled, somebody who has cerebral palsy (CP) has no conscious memory of not being disabled – grown up with it, it’s just part of you, you manage it whatever way you can but for somebody who has a massive stroke and suddenly are forced to “join the disabled club – no experience only of what they know that it is not normal to be disabled – this can be very difficult”. Some disabled people can and do disable themselves – not consciously and this view can be controversial – see (www.disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk – Mason Michelene mason.pdf)”.

Disabled people are not the same as everyone else, just like non-disabled people are not the same as there non-disabled counterparts. Are you normal me or normal like you? Disabled people are unique, our impairments are unique, and they look different in every individual. “My CP (Fiona Weldon) is different to someone else’s CP”. Phil’s “polio” is different to somebody else’s polio”. The important thing here is that we collectively share the lived experiences of how society manages disability – the systems – can be eradicated, but only by us.

We need not to allow the barriers that try to control us and service us to define who we are, or how we should live. It IS NOT OK that a doctor/clinician “has the power to determine our lives”. But the Disability Movement has brought us together. We are sharing our lived experiences, we are supporting one another, and empowering each other to fight the system and tell “the powers that be” what we need – what we want – see (www.youtube.com – Declaration of Independence).

Phil told the group that there is a very clear distinction between talking to a disability activist’ group and talking to a non-disabled group because they don’t have the lived experience. We do have non-disabled allies; and they want to help us because “they get it” but they cannot speak for us – they work with us or not at all. We also need to (as activists):

- Identify clearly who our enemies are – Phil’s work in the past has involved disabled people’s right to employment and the employers were the “oppressor’s”- know who is on our side and who is not

- Be very clear about what right/s you are working towards – be as precise as you can

- Be very specific about the way in which you want to tackle the issue that you face as individuals/as groups.

What the Social Model of Disability says is that disabled people are oppressed by a society that does not consider their needs. For example, Phil uses a wheelchair to get around and if “I cannot get into a building because there are steps, who’s fault is it, it’s definitely not mine!”. In the seven years of training an architect gets, only one week is related to disability/accessibility/universal design.

People with impairments are “disabled” by the barriers they come up against every single day – it is that simple. Phil has polio “my legs don’t work, and I want to get the bus, “I have three choices – go and see my doctor and say doctor please fix me because I want to walk, I could go to Lourdes for a miracle cure, or they can redesign the bloody bus”.

Since the discovery of the Social Model, disabled people internationally have campaign tirelessly for changes in the systems that excludes them. In Ireland for example we have the public transport accessibility retrofit programme (amongst’ other things), this is about

- Upgrading bus stops in rural and regional areas

- Upgrading train stations to make them wheelchair accessible

- Providing grant support for the introduction of more wheelchair accessible vehicles (WAVs) into the taxi fleet.

There is also a political will for a fully accessible transport infrastructure – see (www.thejournal.ie – A significant challenge’: Unclear when public transport will be fully accessible & www.gov.ie – Minister Rabbitte reconvenes Transport Working Group under the National Disability Inclusion Strategy) and of course article 9 of the UNCRPD – Phil told us that in the UK the law demands that all buses must be accessible – level access, with audio and visual accessibility features built in. The important thing here is that the buses were changed and not us – we do not need to be cured and here comes something really interesting – Phil “actually quite like’s being disabled, I quite enjoy the status and I don’t want a bloody cure”. If we were to say, “right women (sexism) the only solution to get what you want is to become a man – have a sex change operation and you will be fine, or black people (racism) avoiding this is simple, become white”. How “bloody preposterous, women becoming men and black people becoming white”.

From the mid 18 century, disabled people were viewed as the problem, get yourself fixed, well “I’m (Phil) sorry, I like being who I am, I like being me, OK it can be inconvenient, I’m not saying that it is a bundle of laughs all the time, there are times when I would quite like to be able to walk but the fact of the matter is I’m seventy bloody six now, and I haven’t walked for 73 years, what’s the point”.

What Mike Oliver, and Vic Finklstein (with many others) did, was to challenge the stereotypical view that disability was a bad thing.

But the fact was that society “needed to be fixed”. Separating out the impairment/condition “polio”, from my disability “the way other people view/treat me”. If we look at people with emotional distress conditions or people with down syndrome for example, most don’t have a problem with physically accessing buses, or with steps, but they got an even bigger problem – attitudinal discrimination, far more insidious than climbing steps. A building is easy to fix, but fixing people’s attitudes is a challenge.

50% of disabled people in the UK are unemployed, and its nearly 80% in Ireland – do you think that’s because the buildings are not accessible or is it because of attitudes – see – (www.nda.ie/publications/attitudes/public-attitudes-to-disability-in-ireland-surveys/public-attitudes-to-disability-in-ireland-survey-2017.html*** & www.irishtimes.com – Ireland is no country for disabled people who want to work ESRI Report-1). ATTATUDES I’m afraid!

They are three distinct barriers that the Social Model explores:

- Physical barriers – limits some disabled people e.g., wheelchair users from moving around freely – inside & out

- Attitudinal barriers – negative beliefs and assumptions means that disabled people “don’t get a fair crack of the whip” – IMPORTANT – some of the time attitudes towards disability is not deliberate – “if you have been brought up to feel concern for disabled people, that you want to help disabled people, that you want to look after disabled people” – unconscious bias – see – (www.youtube.com – Unconscious Biases: Shattering Assumptions and Surprising Ourselves). And of course, these are oppressive and very difficult to change “because they are insidious” – you can’t necessarily see them but there. And moreover, the system is sometimes built with the best of intentions (concern, belief that disabled people need to be cared for, pitied for – can’t walk, talk, hear, learn, work, etc…) and that’s the problem. This is a far more difficult thing to change/challenge, to help people understand that what they are doing isn’t helping disabled people – it is making things worse

- The rules – “it just the way it is”, e.g., you will stay in hospital until the doctor says you can go, you cannot do certain things because of the rules – cannot apply to be a teacher because you are not physically fit, you cannot do that because it might be dangerous, you cannot go near heavy machinery because of A,B,C… So, the rules, the way the system works – institutionalised rules and their structures, disable those with impairments.

Disabled People “V” People with Disabilities

Is there a difference – Phil defines himself as a “disabled person” because he is “part of the Disabled People’s Movement”, he is “not part of the peoples with disabilities movement”- is there such a thing?. So, he is making a “political statement” when he says that he is a “disabled person”.

How you define yourself is entirely up to you. It isn’t for anyone to say how you describe yourself, but for Phil and all of us that are involved in ILMI are “campaigners – we want equality, we want social justice” – the same as black people, gay people, or other marginalised groups, e.g., travellers. You don’t hear a black person say I am a person who is black – black lives rights, and this is about black power – it is a political statement, it’s about rights, it’s about social change. Disability is a social construct – see (www.youtube.com – Disability as a Social Construct) and that “is political”. Nearly 80% of people in Ireland who have a thing called a disability/condition/impairment are unemployed, “that is a political outrage”. The only reason they are unemployed is because somebody has decided that they won’t employ them because they have a label called disability.

ILMI is not about running knitting classes, it’s about social change, it’s about building a collective movement, and this is the bedrock of Strategies for Change. The only way we get buses accessible and equal treatment is by changing attitudes “collectively”, changing the rules and making the world a fairer place where disabled people are included and seen as equals.

We are not the problem; non-disabled people are – “they are not all bad, or nasty or even horrible” but they have been allowed to make “the rules”.

They have decided what we can and can’t do and we as disabled people (using the term very deliberately here) must challenge and change this mindset to live the lives we want.

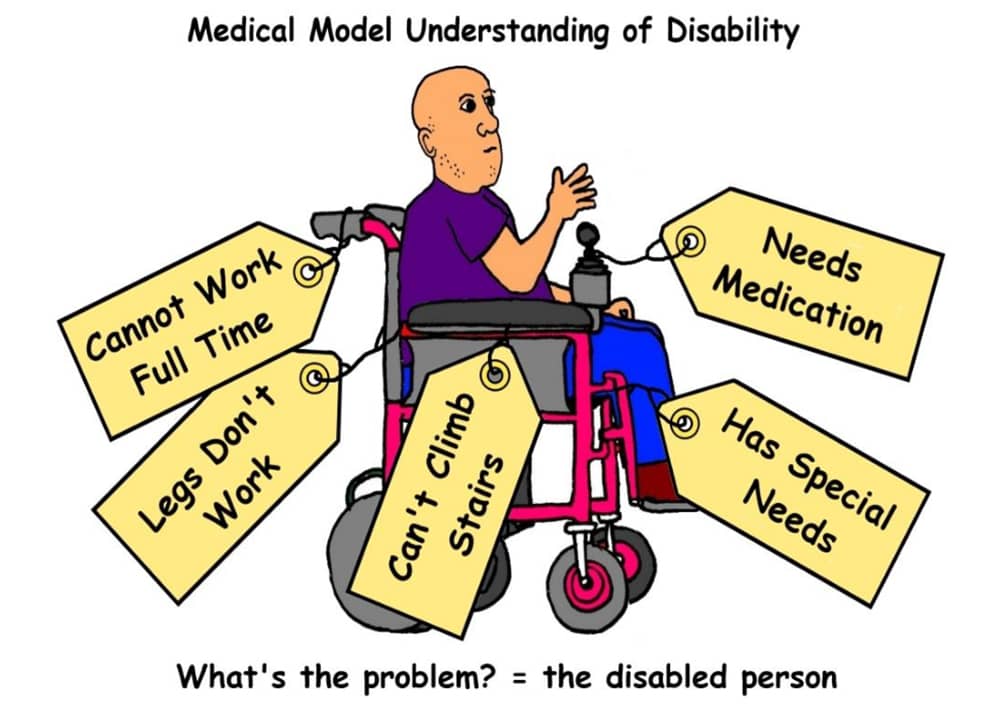

Image: www.semanticscholar.org

Wise Opening Words – In terms of looking at the influence of the individual (medical and charity) model of disability, it is very important that we understand that the influence of the individual model is still being used by many disability support services and mainstream systems to keep “disabled people dependent” rather than enabling them to live ordinary lives.

Sadly, “superiority is the status quo, regardless of what type of disability service we use”.

Paul has worked in many traditional disability services for people with intellectual impairments over the years and told us that trying to change the model of support was exhausting –

“I was constantly coming up against the notion of the adult child and treating them accordingly even though there were no children involved” – it was (and still is) a way of keeping “superiority”.

Paul told us that “sometimes we just need to suck it up” if we are going to make any real change. Also, of importance here is that non-disabled people can be our allies, but they have got to understand that they are OUR EQUALS, and not superior.

Paul invited the group to finish the sentence – Disability Is… feedback included:

- Disability is largely defined and determined by what the majority dictates. In other words, disability is a socially constructed phenomenon.

Q. Are we all disabled in some way – NO WE ARE NOT – Both myself (Fiona) and Paul have been on many courses/meetings/spaces over the years where non-disabled people would say “we are all disabled in some way”??? “That’s kinda nice and flowery but they don’t have to wear our labels and that’s the difference”.

- Disability is society’s labelling system – I remember being asked how disabled I was, and I was like… Oh my God, I didn’t realise that there was a measurement or a scale

We then chatted about the positive things – being “labelled disabled” makes you more courageous, powerful, and resilient

- “It is interesting that people don’t ask you outright if you are straight or gay”, so why do people need to enquire about our impairment labels or level of severity?

- “I am getting more and more angry as time is going on with non-disabled people – I was using my walker again today and a lady was parked on the footpath and she asked me… can you get by – I just couldn’t believe it – it is a pet hate of mine – the lady was parked on a double yellow line – non-disabled people don’t realise – it’s just frustrating” – FYI on the 1st of February this year the Minister for Transport (Eamon Ryan) announced that if you park on a double yellow line then your fine will be doubled.

- Disability is a “mismatch between impairment and societal attitudes and environment barriers”

- We should “as disabled people” be able to give out parking fines” – this would be a great income generator – employ disabled people

- Sometimes “disability activism can be depressing, I spent the last seven years attempting to be an activist – people don’t listen, they don’t attempt to really understand…it’s just exhausting trying to explain the basic things repeatedly, I have sacrificed a lot… and it can wear you down…”.

One of the things that encouraged Paul to get involved with this programme was the prospect of meeting other activists. “I think the only way that we can survive is by rejuvenating each other and encouraging each other and that’s where the formation of the disability movement came from. It was disabled people empowering each other”.

The Individual Model – Charity/Medical Model of Disability

Look at the social model of disability (opposite to the individual model) for a moment, and the reason it is the foundation of the disability movement. Paul was introduced to the social model of disability about 40 years ago and it changed his life – it was truly the most liberating experience he’d ever had because he no longer had to be apologetic.

It enabled him to challenge and question which is important but moreover to do something.

“I spent years going around with handcuffs in my pocket because we used to handcuff ourselves to the underground and block traffic”.

The social model of disability enabled him to learn from other disabled activists and link in with similar minded people.

The individual model (combination of the medical and charity model) was created by medical/clinical professionals in the nineties. It locates the “problem within the individual”. This model doesn’t consider who we are as people, or as human beings. Disability is seen as an illness, and it focuses on fixing us, or finding a cure, and if this doesn’t work, we get ousted. The individual model preserves the negative assumptions (that society holds) about who we are, and what we can/cannot do.

Some of these negative assumptions include:

- We are looked upon as being sick and “just being sick can often be linked to our impairment label”

- We need specialist/professional help and that comes at a bigger price (perceived) – that’s where charities come in

- We need to be segregated from society – specialised care

- We are confined to our wheelchairs or wheelchair bound

- We are less than, less able, less intelligent, not at all “normal”, and there is something wrong with us

- We cannot learn or hold down a job

- The medical profession and clinicians know best, we are expected to be passive and behave accordingly

- We are pitied and seen as “special”.

How do you think these models affect disabled people’s lives?

Feedback from discussion:

- Completely “drains your confidence”, self-belief, self-worth

- We are forced to feel different; “forced to blame ourselves”

- Encourages “people to feel sorry for us”

- Encourages us (disabled people) to “feel sorry for ourselves”

- A belief – “who would employ us” – loss of employment upon acquiring an impairment

- Told what to do, “voiceless”

- “Less worthy” than non-disabled people

- Frustrated

- Forced to go to a special school, taken out of class to go to a special class – disabled people have special needs???

- Must prove your impairment when applying for things – driving licences for example

- Can force disabled people’s organisations to become charity identities

- Feel totally invisible

- Burdened or feeling like you are a burden to your family and society

- Our needs are not considered – accessibility – environmental, information in formats that some disabled people need, inclusive education, transport, the right to live as our non-disabled counterparts do, etc…

- Perpetuates difference – feeling ashamed

- Voice not heard, not listened too

- Are labelled and put in a box

- Allows non-disabled people to be “in control”, to hold all the power

- Being forced to be medically assessed over and over again

- Perpetuates pity and begging for money (charity) – big organisations use begging for us and USE US to do this

- HSE funding disability services (run by non-disabled people/professionals) that is built around the individual model

- It’s a “nightmare” to apply and gain meaningful employment

- No real political interest to insure equality

- The cost (treatment & financial) to the lives of those that are labelled disabled and their families.

So, disability is a form of discrimination based on our impairments – if disabled people were able to participate fully and equally in society then our impairments would be irrelevant.

Paul remembers when he was conducting a review of the public service centres in Donegal – I interviewed staff and service users and one interviewee…a man who had MS – he said – “I went to use the public service centre… and there was someone parked in the disabled parking zone, so I was forced to park further away, and I fell and hurt myself and I went home and cried”. The man told Paul that the problem was his MS and not the fact that somebody was parked in the disabled parking zone.

The individual model makes people blame themselves, disabled people are forced to focus on what’s wrong with them. Paul asked the man if he did anything (complained) which is about action rather than internalising the situation and blaming himself.

Discrimination & Stigma

Disability discrimination (sometimes known as ableism) is a bias or prejudice against disabled people.

It can take the form of negative ideas and assumptions, stereotypes, attitudes and practices, physical barriers in the environment, and result in large scale oppression – treating disabled people as less than and put them at a disadvantage for being labelled disabled.

Stigma is a form of negative social labelling that tends to exclude a stigmatised group from society. If someone or something is stigmatised, they are unfairly regarded by the majority as being bad or having something to be ashamed of, they are viewed as being not normal and have a spoiled identity. This leads to groups of people being excluded from power, wealth, and having valued social roles within society – disabled people are one of these groups.

Thus, stigma supports and maintains the status quo in a society where one layer of a system continues to oppress another. Stigma can give rise to several different kinds of negative responses. At one end of the scale the stigmatised person is seen as a helpless object of pity to be talked about and cared for. And at the other extreme the disabled person is seen as an object of fear and dread to be avoided, shunned, or restrained or locked away. Either way, the person is denied recognition of their true capabilities.

The Difference Between Impairment and Disability

The reality is that most of the time we can’t change our physical, intellectual, sensory, or emotional distress impairment but we can challenge and change the discrimination (disability) that we experience.

We as activists must fight history. There is an insurmountable amount of research that informs us that “disabled people are the most marginalised group in the world”. So, we (disabled people) either fight between ourselves to decide “who gets what” or work collectively to insist that we get the same rights and the same status as our non-disabled counterparts.

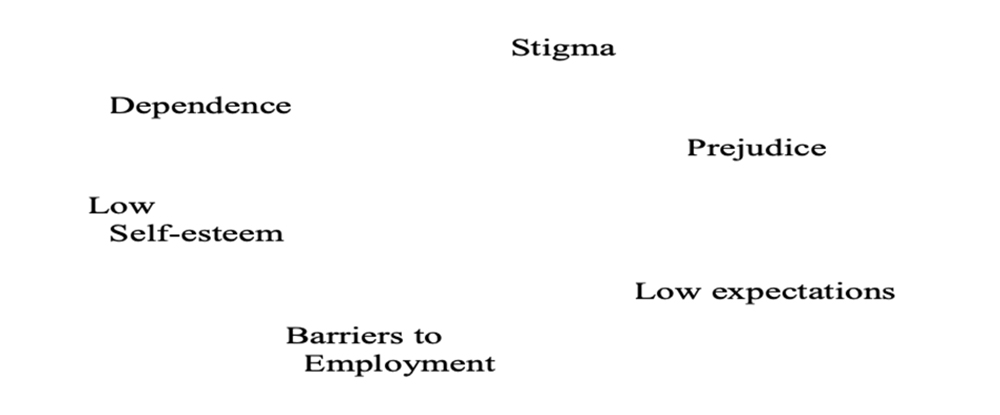

The Impact of Disabling Barriers

There are so many barriers that disabled people have to go through just to live an ordinary life – see below diagram

Because of negative social beliefs and attitudes, a lot of disabled people may experience a vicious circle of stigma and prejudice which can affect how they think of themselves

As disabled people we need to be aware of these negative beliefs and attitudes and how they can impact our lives – it is about recognising THE BARRIERS in order to address them individually/collectively and become strong and united; we need to nurture and empower each other to fuel our strength.

Another important conversation that we need to have with ourselves is to look at the labels that have been assigned to us by the majority – we either let these “labels” influence our lives or we challenge them and fight against them.

We also need to be mindful that “disability” in terms of “servicing disabled people (disability services doing things for us, not with us and speaking for us/about us and not with us) is a billion-euro industry” and the individual model of disability is at its core – run by and controlled by sometimes “very nice non-disabled professionals”. But “being very nice does not liberate us from the systems that oppress us, so they must either become our allies and recognise the power that we (disabled people) should have or move aside and let us through”. We are more than capable and are only too willing to take over and use our lived experiences as knowledge to create systems that genuinely include all disabled people.

Paul invited the group to look at their challenging discrimination stories

Feedback included:

- Upon completion of my degree, I decided to do a Masters. I applied and met with the head of the programme, and I was basically told “because of my visual impairment you won’t be able to study the classical languages involved…”.

At the time I didn’t have any reference to the social model of disability – “the assumption was because of my visual impairment I wouldn’t be capable of studying languages”. - Parking – when somebody tells me I don’t need to use a disabled parking bay, or I question a non-disabled person parked in one and they say “I’m only going to be a minute” … “I feel sick … belittled”

- When people make fun of me, or they don’t accommodate me, sometimes I get “you don’t have autism”. Some people “don’t allow themselves time to understand me… feel what I say is not valid”, some people have no patience when it comes to disabled people”

- Signed up to “teach undergraduates during my masters, but I was refused because of my speech impairment”

- I was refused work just because “I wouldn’t be able to carry boxes. I did challenge them – I told them that “the boxes could be delivered, and I would ensure the work would be carried out via giving directions to a person helping me, but they were not happy with this”… “I have taken action since with a hotel – disabled toilet constantly locked, so I had to go to reception for the key again and again”. “Now I’m dealing with a car rental company that discriminated against me because they were not able to provide me with the hand controls that I needed…

I managed to get them to pay a secondary company for my car hire at no extra cost and change their company policy”… - “The company I worked for amalgamated… as a result they didn’t know what to do with me, it was the most humiliating experience of my life…I had both the experience and the knowledge to carry out my job, it was sole destroying”…

- In “transition year I discovered that I could paint using my mouth, so I did art for my leaving certificate – I was unable to do the life drawing part of the art exam because it was so intricate – my teacher wanted to support me…but the principal wouldn’t allow it, so I got very low marks”…

- In secondary school I was diagnosed with dyslexia (I had previously gotten diagnosed with dyspraxia in primary school) and the attitude of other students… I felt quite bad… it was like the diagnosis wasn’t real”…

- I attended an educational centre for disabled people a few years back, and they tried to force me to attend five days a week and I knew I wouldn’t be able… I had a bad fall one day (because of fatigue) and it took a good old fashioned Irish mammy to sort them out… I ended up attending three days and fitted the study in”…

- When “I was in college, and I was given a personal assistant – always late or absent… I was in the middle of writing my paper …very different situation. I decided to go to the disability support services within the college…I presumed that they were going to be on my side… but they decided what I needed support in, and what I didn’t need support in, and I should be thankful???”.

It is much better to challenge the discrimination that we experience and fight for our rights then internalise it and beat ourselves up – it really affects our health and wellbeing

“The whole idea of disability as an excuse to discriminate***** – all of my friends have impairments (allergies to peanuts, to cats and the rest) but society isn’t set up for that to be a problem i.e., it’s not like you need to be around cats to participate in society. Sure, it’s a pain, it’d be nice to eat peanuts or stroke cats but that’s not limiting”.

A Brief Look at the Media

The media has focused on portraying impairment through the influence of the individual model of disability. What we see, hear, and read is often decided and influenced by a small group of people – “editors, producers, programmers and budget-controllers are swayed by their own opinions of disability and what they believe will bring in audiences”.

Historically media examples containing disabled people have largely conformed to negative stereotypes. We will be looking at this topic in more detail in a future session.